کانون دانش زبان This weblog has been created to handle the institute programs جمعه 1 آذر 1392برچسب:, :: 8:49 :: Writer : English Teachers

English is a West Germanic language that originated from the Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Britain by Germanic invaders and/or settlers from various parts of what is now northwest Germany and the Netherlands. Initially, Old English was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Britain. One of these dialects, Late West Saxon, eventually became predominant. The English language underwent extensive change in the Middle Ages. Written Old English of AD 1000 is similar in vocabulary and grammar to other old Germanic languages such as Old High German and Old Norse, and completely unintelligible to modern speakers, while the modern language is already largely recognisable in written Middle English of AD 1400. The transformation was caused by two further waves of invasion: the first by speakers of the Scandinavian branch of the Germanic language family, who conquered and colonised parts of Britain in the 8th and 9th centuries; the second by the Normans in the 11th century, who spoke Old Norman and ultimately developed an English variety of this called Anglo-Norman. A large proportion of the modern English vocabulary comes directly from Anglo-Norman. Close contact with the Scandinavians resulted in a significant grammatical simplification and lexical enrichment of the Anglo-Frisian core of English. However, these changes had not reached South West England by the 9th century AD, where Old English was developed into a full-fledged literary language. The Norman invasion occurred in 1066, and when literary English rose anew in the 13th century, it was based on the speech of London, much closer to the centre of Scandinavian settlement. Technical and cultural vocabulary was largely derived from Old Norman, with particularly heavy influence in the church, the courts, and government. With the coming of the Renaissance, as with most other developing European languages such as German and Dutch, Latin and Ancient Greek supplanted Norman and French as the main source of new words. Thus, English developed into very much a "borrowing" language with an enormously disparate vocabulary.

Proto-English[edit]The languages of Germanic peoples gave rise to the English language (the best known are the Angles, Saxons, Frisii, Jutes and possibly some Franks, who traded, fought with and lived alongside the Latin-speaking peoples of the Roman Empire in the centuries-long process of the Germanic peoples' expansion into Western Europe during the Migration Period). Latin loan words such as wine, cup, and bishop entered the vocabulary of these Germanic peoples before their arrival in Britain and the subsequent formation of England.[1] Tacitus' Germania, written around 100 AD, is a primary source of information for the culture of the Germanic peoples in ancient times. Germanics were in contact with Roman civilization and its economy, including residing within the Roman borders in large numbers in the province of Germania and others and serving in the Roman military, while many more retained political independence outside of Roman territories. Germanic troops such as Tungri, Batavi and Frisii served in Britannia under Roman command. Except for the Frisians, Germanic settlement in Britain, according to Bede, occurred largely after the arrival of mercenaries in the 5th century. Most Angles, Saxons and Jutes arrived in Britain in the 6th century as Germanic pagans, independent of Roman control, again, according to Bede who wrote his Ecclesiastical History in 731 AD. Although Bede mentions invasion by Angles, Saxons and Jutes, the precise nature of the invasion is now disputed by some historians, and the exact contributions made by these groups to the early stages of the development of the English Language, are contested.[2] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relates that around the year 449 Vortigern, King of the Britons, invited the "Angle kin" (Angles allegedly led by the Germanic brothers Hengist and Horsa) to help repel invading Picts. In return, the Anglo-Saxons received lands in the southeast of Britain. In response "came men of Ald Seaxum of Anglum of Iotum" (Saxons, Angles and Jutes). The Chronicle refers to waves of settlers who eventually established seven kingdoms, known as the heptarchy. Modern scholars view Hengist and Horsa as Euhemerised deities from Anglo-Saxon paganism, who ultimately stem from the religion of the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[3] However it is important to remember that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was not a contemporaneous record of these assumed folk-movements. It was first written around 850 AD, up to four hundred years after the events it is describing. Therefore we cannot assume that the Chronicle is an accurate record for the fifth and sixth centuries, or that the events referred to actually took place

Old English – from the mid-5th century to the mid-11th century[edit]

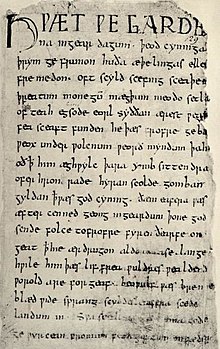

The first page of the Beowulf manuscript

Main article: Old English

After the Anglo-Saxon invasion, the Germanic language possibly displaced the indigenous Brythonic languages and Latin in most of the areas of Great Britain that later became England. The original Celtic languages remained in parts of Scotland, Wales and Cornwall (where Cornish was spoken into the 19th century), although large numbers of compound Celtic-Germanic placenames survive, hinting at early language mixing.[5] Latin also remained in these areas as the language of the Celtic Church and of higher education for the nobility. Latin was later to be reintroduced to England by missionaries from both the Celtic and Roman churches, and it would, in time, have a major impact on English. What is now called Old English emerged over time out of the many dialects and languages of the colonising tribes.[6] Even then, Old English continued to exhibit local variation, the remnants of which continue to be found in dialects of Modern English.[6] The most famous surviving work from the Old English period is the epic poem Beowulf composed by an unknown poet. Old English varied widely from modern Standard English. Native English speakers today would find Old English unintelligible without studying it as a separate language. Nevertheless, English remains a Germanic language, and approximately half of the most commonly used words in Modern English have Old English roots. The words be, strong and water, for example, derive from Old English. Many non-standard dialects such as Scots and Northumbrian English have retained features of Old English in vocabulary and pronunciation.[7] Old English was spoken until some time in the 12th or 13th century.[8][9] In the 10th and 11th centuries, Old English was strongly influenced by the North Germanic language Old Norse, spoken by the Norsemen who invaded and settled mainly in the North East of England (see Jórvík and Danelaw). The Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians spoke related languages from different branches of the Germanic family; many of their lexical roots were the same or similar, although their grammars were more divergent. The Germanic language of the Old English-speaking inhabitants was influenced by extensive contact with Norse colonizers, resulting perhaps in cases of morphological simplification of Old English, including the loss of grammatical gender and explicitly marked case (with the notable exception of the pronouns). English borrowed approximately two thousand words from Old Norse, including anger, bag, both, hit, law, leg, same, skill, sky, take, and many others, possibly even including the pronoun they.[10] The introduction of Christianity late in the 6th century encouraged the addition of over 400 Latin loan words, such as priest, paper, and school, and fewer Greek loan words.[11] The Old English period formally ended some time after the Norman conquest (starting in 1066 AD), when the language was influenced to an even greater extent by the Normans, who spoke a French dialect called Old Norman. The use of Anglo-Saxon to describe a merging of Anglian and Saxon languages and cultures is a relatively modern development. Middle English – from the late 11th to the late 15th century[edit]Main article: Middle English

Further information: Middle English creole hypothesis

For centuries following the Norman Conquest in 1066, the Norman kings and high-ranking nobles spoke one of the French langues d'oïl, that we call Anglo-Norman, a variety of Old Norman used in England and to some extent elsewhere in the British Isles during the Anglo-Norman period and originating from a northern langue d'oïl dialect. Merchants and lower-ranked nobles were often bilingual in Anglo-Norman and English, whilst English continued to be the language of the common people. Middle English was influenced by both Anglo-Norman and, later, Anglo-French (see characteristics of the Anglo-Norman language). In this period, the French language was regarded like an official language in England, but this tendency would disappear in the 14th century.[12] Even after the decline of Norman-French, standard French retained the status of a formal or prestige language—as with most of Europe during the period—and had a significant influence on the language, which is visible in Modern English today (see English language word origins and List of English words of French origin). A tendency for French-derived words to have more formal connotations has continued to the present day. For example, most modern English speakers consider a "cordial reception" (from French) to be more formal than a "hearty welcome" (from Germanic). Another example is the rare construction of the words for animals being separate from the words for their meat, e.g., beef and pork (from the French bœuf and porc) being the products of "cows" and "pigs"—animals with Germanic names. English was also influenced by the Celtic languages it was displacing, especially the Brittonic substrate, most notably with the introduction of the continuous aspect (to be doing or to have been doing), which is a feature found in many modern languages but developed earlier and more thoroughly in English.[13] While the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle continued until 1154, most other literature from this period was in Old Norman or Latin. A large number of Norman words were taken into Old English, with many doubling for Old English words. The Norman influence is the hallmark of the linguistic shifts in English over the period of time following the invasion, producing what is now referred to as Middle English. English literature reappeared after 1200, when a changing political climate and the decline in Anglo-Norman made it more respectable. The Provisions of Oxford, released in 1258, was the first English government document to be published in the English language after the Norman Conquest. In 1362, Edward III became the first king to address Parliament in English. By the end of the century, even the royal court had switched to English. Anglo-Norman remained in use in limited circles somewhat longer, but it had ceased to be a living language.

Opening prologue of The Wife of Bath's Tale Canterbury Tales.

Geoffrey Chaucer is the most famous writer from the Middle English period, and The Canterbury Tales is his best-known work. Although the spelling of Chaucer's English varies from that of Modern English, his works can be read with minimal assistance. The English language changed enormously during the Middle English period, both in grammar and in vocabulary. While Old English is a heavily inflected language (synthetic), an overall diminishing of grammatical endings occurred in Middle English (analytic). Grammar distinctions were lost as many noun and adjective endings were leveled to -e. The older plural noun marker -en largely gave way to -s, and grammatical gender was discarded. Approximately 10,000 French (and Norman) loan words entered Middle English, particularly terms associated with government, church, law, the military, fashion, and food.[14] English spelling was also influenced by Norman in this period, with the /θ/ and /ð/ sounds being spelled th rather than with the Old English letters þ (thorn) and ð (eth), which did not exist in Norman. These letters remain in the modern Icelandic alphabet, having been borrowed from Old English via Western Norwegian. Early Modern English – from the late 15th to the late 17th century[edit]Main article: Early Modern English

The English language underwent extensive sound changes during the 1400s, while its spelling conventions remained rather constant. Modern English is often dated from the Great Vowel Shift, which took place mainly during the 15th century. English was further transformed by the spread of a standardised London-based dialect in government and administration and by the standardising effect of printing. Consequent to the push toward standardization, the language acquired self-conscious terms such as "accent" and "dialect".[15] By the time of William Shakespeare (mid 16th - early 17th century),[16] the language had become clearly recognisable as Modern English. In 1604, the first English dictionary was published, the Table Alphabeticall. Increased literacy and travel have facilitated the adoption of many foreign words, especially borrowings from Latin and Greek since the Renaissance. (In the 17th century, Latin words were often used with the original inflections, but these eventually disappeared). As there are many words from different languages and English spelling is variable, the risk of mispronunciation is high, but remnants of the older forms remain in a few regional dialects, most notably in the West Country. During the period, loan words were borrowed from Italian, German, and Yiddish. British acceptance of and resistance to Americanisms began during this period.[17] Modern English – from the late 17th century to the present[edit]Main article: Modern English

The Dictionary of the English Language was the first full featured English dictionary. Samuel Johnson published the authoritative work in 1755. To a high degree, the dictionary standardized both English spelling and word usage. Meanwhile, grammar texts by Lowth, Murray, Priestly, and others attempted to prescribe standard usage even further. Early Modern English and Late Modern English vary essentially in vocabulary. Late Modern English has many more words, arising from the Industrial Revolution and the technology that created a need for new words as well as international development of the language. The British Empire at its height covered one quarter of the Earth's surface, and the English language adopted foreign words from many countries. British English and American English, the two major varieties of the language, are spoken by 400 million persons. Received Pronunciation of British English is considered the traditional standard, while General American English is more influential. The total number of English speakers worldwide may exceed one billion.[18] l Phonological changes[edit]Main article: Phonological history of English

Grammatical changes[edit]The English language once had an extensive declension system similar to Latin, modern German or Icelandic. Old English distinguished between the nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive cases, and for strongly declined adjectives and some pronouns also a separate instrumental case (which otherwise and later completely coincided with the dative). In addition, the dual was distinguished from the more modern singular and plural.[19] Declension was greatly simplified during the Middle English period, when the accusative and dative cases of the pronouns merged into a single oblique case that also replaced the genitive case after prepositions. Nouns in Modern English no longer decline for case, except for the genitive. Evolution of English pronouns[edit]"Who" and "whom", "he" and "him", "she" and "her", etc. are a conflation of the old accusative and dative cases, as well as of the genitive case after prepositions. This conflated form is called the oblique case, or the object (objective) case because it is used for objects of verbs (direct, indirect, or oblique) as well as for objects of prepositions. (See object pronoun.) The information formerly conveyed by having distinct case forms is now mostly provided by prepositions and word order. In Old English as well as modern German and Icelandic as further examples, these cases had distinct forms. Although the traditional terms accusative and dative continue to be used by some grammarians, these are roles rather than actual cases in Modern English. That is, the form whom may play accusative or dative roles (or instrumental or prepositional roles), but it is a single morphological form and therefore a single case, contrasting with nominative who and genitive whose. Many grammarians use the more intuitive labels 'subjective', 'objective', and 'possessive' for nominative, oblique, and genitive pronouns. Modern English nouns distinguish only one case from the nominative, the possessive case, which some linguists argue is not a case at all, but a clitic (see the entry for genitive case for more information).

نظرات شما عزیزان:

|

|||||||||||||||||

Writers

links

last

|

|||||||||||||||||

آمار

وب سایت:

آمار

وب سایت: